Grafite em Curitiba (Photo: Fernando Rosa, January 18, 2013)

http://alturl.com/8dzyq

How would cities look if urban planners, not politicians, were in charge?

Recycle City: The Road to Curitiba (New York Times, May 20, 2007)

Planning from the Outside

The long history of the city of Curitiba, in southern Brazil, demonstrates that it is perhaps the most heavily planned city in the western hemisphere. The layout of the original town, like many such colonial developments in the Americas, had been heavily influenced by the Laws of the Indies — a set of precepts from the 16th Century that dictated much of the governance of Spanish and Portuguese land holdings; which included rules for town planning. And, though Brazil gained independence from Portugal in the 1820’s it’s various cities were still governed by many of the land use laws inherited from its former European ruler.

Even 250 years after its founding (and 120 years after Brazilian independence), Curitiba’s first true Master Plan was still developed, not by locals but, by the French architect and sociologist Alfred Agache in 1943 — a Beaux-Arts trained architect who was a leading theorist, teacher and practitioner of the Société Française des Urbanistes (SFU).

“Planning – as we have often said in our conferences – is both a science, an art and a philosophy; A science because it proceeds from the systematic review of the facts based on a detailed study of the pasts of cities and their characteristics. The Planner’s next step is to investigate the causes of development or discomfort; and finally, only after a specific detailed analysis, is it possible to provide for the required improvements for the future development of the city. Observation, classification, analysis and synthesis — all required characteristics of a scientific study. ” … “But if science alone could solve the problems of city planning, urbanization could undoubtedly be reduced to a number of formulas. It is not so. Urbanism is also an art because the intuition, imagination, and composition play an important role in its application: the Planner must translate into proportion, volumes, perspectives, silhouettes, the various proposals suggested by engineers, economists, public health concerns and financial constraints.” … “Urbanism is also in the field of social philosophy — The city, in fact, seeks to achieve plastically the appropriate framework for the existence of an organized community.” Alfred Agache, 1932

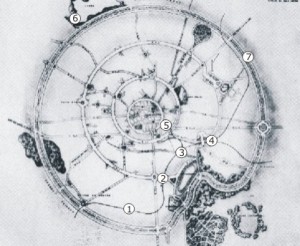

Alfred Agache’s plan for Curitiba (Alfred Agache, 1943)

http://tinyurl.com/lvssvbm

Agache’s plan for Curtiba was profoundly influenced by Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City concept, borrowing the following elements:

- A Central Railway

- A Perimeter Avenue

- Interstitial support avenues

- A Central Railway station located on the Perimeter Avenue

- A main avenue leading from the Central Railway station to the City Center.

- A series of parks located beyond the city, and

- A peripheral greenbelt Park Avenue that would connect all the city parks.

Agache’s plan assumed a maximum population for Curitiba of no more than 900,000 people, all residing in buildings constructed to be between six to eight stories in height. Understandably, this would have resulted in a fairly compact city.

This time around, the plan would be local-grown.

Even though the town’s population had only reached 430,000 by 1960 it had already outpaced the land area envisioned in the Agache Plan (essentially by growing less densely). Spurred on by residents’ concerns over the loss of easily accessible green space and the loss of the city’s unique character, in 1964 the mayor of Curitiba (Ivo Arzua) issued a call for proposals for a new plan for the city.

This time around, the initial plan was prepared by an energetic group of local professionals led by Jaime Lerner — a 27 year old local who had just graduated from architecture school. The following year, Learner help form the city’s first-ever planning department, the Institute of Urban Planning and Research of Curitiba (abbreviated the IPPUC in Portuguese). Over the next few years the Lerner-led IPPUC refined the initial plan, readying it for the city’s adoption in 1968.

This new, local plan for the city lead to nothing less than a revolution in urban planning.

If you want to make life better for people, make the cities better for people. Jaime Lerner

This new plan more fully integrated transportation planning and land use planning, as well as tying social welfare programs for some of the poorest residents to the development of the city.

Transportation as the backbone for sustainable practices

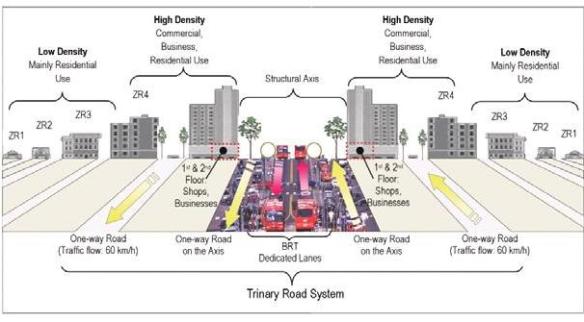

Curitiba’s Trinary Road System (IPPUC, accessed 2014) http://tinyurl.com/n79qt3b

By 1974 the reorganization of the city’s road system into a new hierarchical network was implemented; this included the formation of a radically new road type — one whose central component is a mass transit spine. Unlike similar network systems in the United States and elsewhere, where the lead position in such a hierarchy is the limited-access Freeway, in Curtiba the position is held by the Sistema Trinário (or, Trinary Road System). These five trinary road corridors, radiating outward and encircling the city, are actually composed of three parallel road sections. The two outer roads are for local vehicles and pedestrians (serving as a paired one-way couplet) while the central road is a wider road section composed of two outer one-way streets and an inner two-directional street reserved exclusively for bus mass transit.

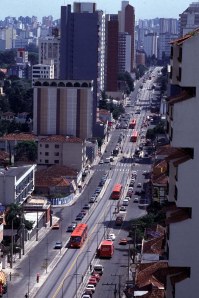

Curitiba’s Trinary Road – Avineda Joao Gualberto (Photo: Joel Rocha, 2014)

http://alturl.com/ny6xq

The picture to the left shows the development surrounding the central spine road of one of the Trinary Road network.

This full-integration of transit accommodations in the road design itself allows the buses running along the central spine to operate at a level of efficiency similar to that of rail transit.

It’s asserted by proud Curitibanos that if you miss your bus, you have to wait all of 90-seconds to catch your next ride.

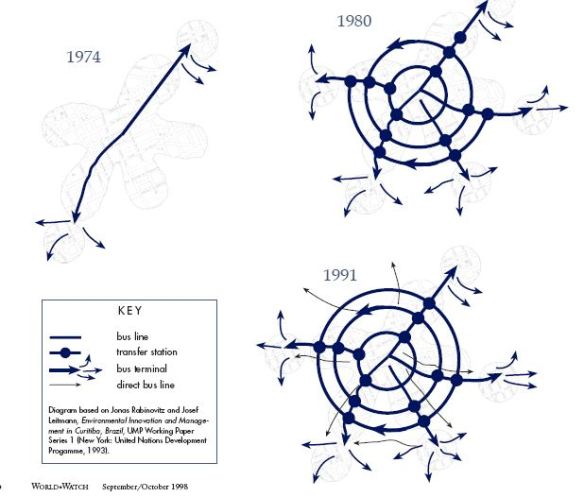

In less than 20 years, this Trinary Road System, with its integrated Bus Rapid Transit System, was expanded to cover the entire city.

Evolution of Curitiba’s Transportation System (Jonas Rabinovotz and Josef Leitmann, 1993)

Curitiba’s BRT was constructed at a cost of only $200,000 per kilometer, nearly 450-times less than the cost of a new subway, and it transports 2.3 million passengers a day, not bad for a city with a population of 1.75 million.

With such success, Curitiba’s BRT system has heavily influenced the development of similar transit systems throughout the world.

Other Sustainability Efforts

As part of the municipal plan, the city has pushed other sustainability efforts. These include a dramatic increase in the amount of green space per resident, and some innovative efforts like the “garbage that’s not garbage” program that trades fresh vegetables for trash brought in for recycling.

Even Bill McKibben, the American environmentalist, has written about the environmental and social successes of Curitiba.

The Downside of Success

Although the city has undergone quite a renaissance since the adoption of its own locally grown plan, there have been some recent setbacks.

The Atlantic Cities blog recently published an article titled, Has South America’s Most Sustainable City Lost Its Edge?, which highlights a recent 4.3% decline in BRT ridership, and emerging failure to more fully integrate its suburbs into a more coherent regional plan.

Stefan Gruber, the Austrian architecture and urbanism professor, has written that the city’s more paternalistic attitude towards its citizens (and resultant lack of democratic outreach) has hobbled the city’s ability to elicit a sense of civic responsibility among its residents.

Conclusion

As American towns struggle to implement sustainability and livability measures, Curitiba’s frugal example of putting the needs of the people first in all its planning efforts is worth emulating.

Curitiba as Vita the Turtle (Jaimer Lerner, 2006)

http://alturl.com/6gvqo

While the city does loose marks for its comparative lack of democratic input from its citizens (compared to other Brazilian cities), the IPPUC does engage in extensive outreach as it develops its plans (far more than most U.S. cities).

From its focus on social, environmental, and transportation improvements — all through the lens of free enterprise (its BRT system runs with very minimal government subsidy) — Curitiba may provide the best example for growing towns throughout the American West.

Downtown Curitiba (Photo: Francisco Anzola, Feburary 3, 2010)

http://alturl.com/jbqk7

Great article. I had not heard about Curitiba before, but now I’ll be doing more research on this unique city. I find it amazing what planning and putting people first can do for a city. Now if only the car-centric people of Boise could realize this…

Thanks Martin,

I had the pleasure of meeting Jaime Lerner a few years back at a CNU conference in Seattle. I agree with you regarding the lessons we can learn from Curitiba – especially in regards to Bus Rapid Transit. Another south-of-border metropolis we can learn from is Bogeta – that has accomplished wonders through participatory budgeting. The city’s former mayor (Enrique Penalosa) was interviewed in a great, recent, documentary “Urbanism” – if you have the time I’d recommend watching this wonderful film.